While tourism is often considered a means to preserve Indigenous cultures, it actually helps perpetuate those cultures, says Camille Ferguson in the September/October cover story of Destinations magazine, “It Takes a Village: As Indigenous-led tourism grows, more truth is told, more lessons are learned, and reconciliation begins.” Ferguson currently serves as economic development director of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska and has been involved in cultural tourism for 35 years, working as a tour guide for a motorcoach company, helping the Sitka Tribe of Alaska develop a Tribal Tour Cultural program, heading up AIANTA as executive director, and serving on the board of the Alaska Travel Industry Association. “When I first started, it was not to preserve our culture,” she says. “We were already preserving culture very well in museums. The reason tourism is important is it’s a means to keep our culture alive.”

Traditional ceremonies, songs, and dances are competing with Western sports, entertainment, and video games for Indigenous youths’ attention. “Tourism gives us an opportunity to teach our youth, and then have them be the teachers by dancing, doing their art, and answering visitors’ questions,” says Ferguson. “They’re actually learning, and they are being compensated as well.”

A dugout canoe at the “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea” exhibit at the Mystic Seaport Museum.

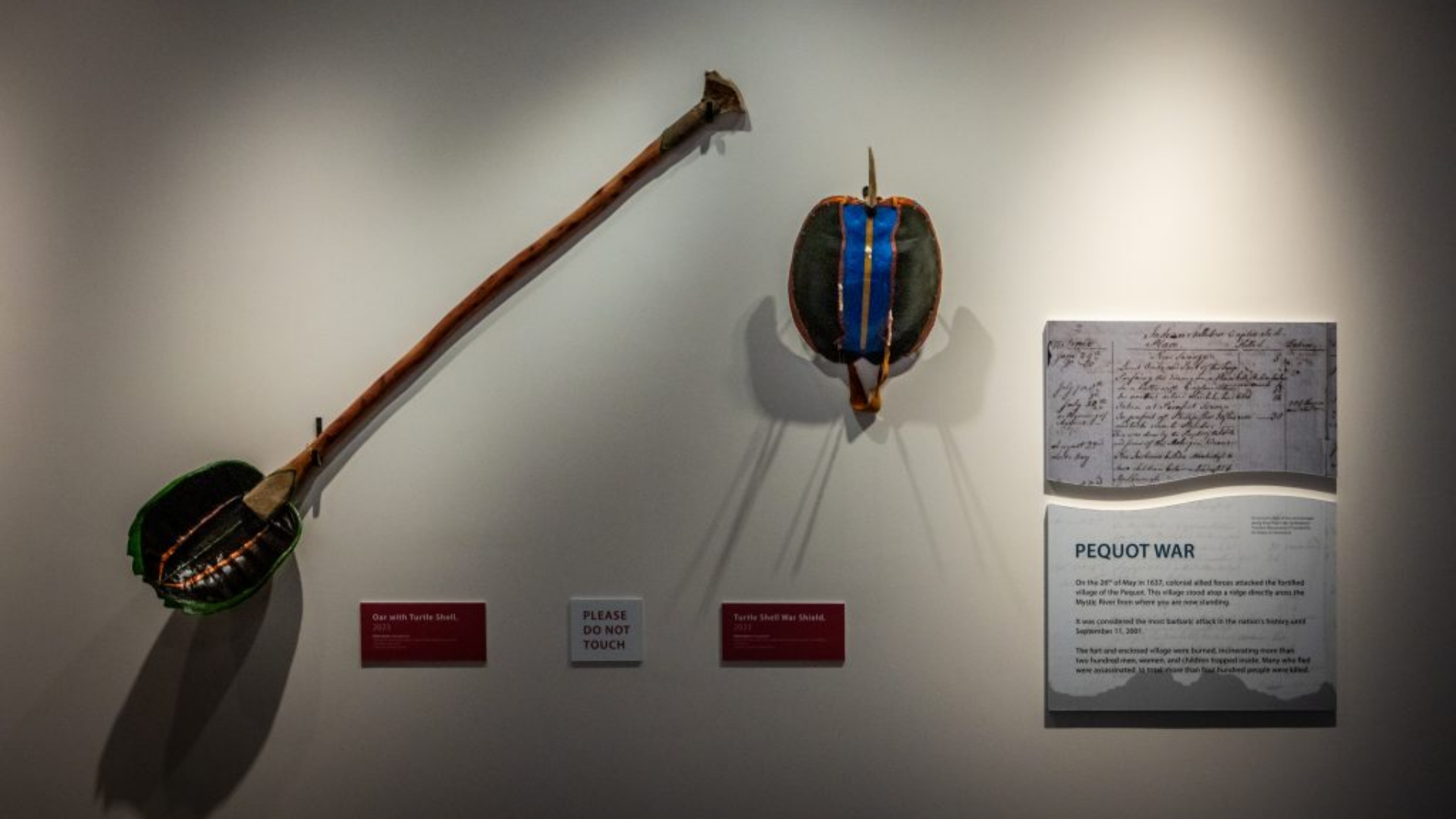

Pequot War display at the “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea” exhibit at the Mystic Seaport Museum.

At the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut, groups now have the chance to sit in a real dugout canoe or walk inside a wetu—a domed house made with a frame of red cedar—thanks to “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea,” a major exhibition that explores the maritime histories and contributions of Indigenous communities, African civilizations, and people of African descent. The exhibit is part of a broader project called Reimagining New England Histories.

“The dugout canoe was created during a residency with Mashantucket Pequot, Mashpee Wampanoag, Ghanaian, and Togolese boat makers,” says Akeia de Barros Gomes, Ph.D., William E. Cook vice president of the American Institute for Maritime Studies at Mystic Seaport Museum. “Because on both sides of the Atlantic, dugout canoes were made using the same method of hollowing out with fire and water.”

Once visitors pass the canoe, “That entire open space is about our 12,000-plus years of maritime history and culture, and how those things enabled us to survive—despite what, timewise, is a very brief interruption of colonialism, slavery, and dispossession,” says de Barros Gomes. It includes everything from artifacts dating back 2,500 years to contemporary art pieces created by Indigenous and African-descended artists.

Read More!

Read the September/October 2024 Destinations cover feature, “It Takes a Village,” for a more in-depth look!

The wetu is actually half of a wetu, about 15 feet across. It’s a half-hemisphere built against one of the exhibit’s walls by SmokeSygnals, a Native American creative agency on Cape Cod. They could have built an entire wetu and cut it in half, but that would have extracted additional cedar from the environment that would only be thrown away.

SmokeSygnals took Mashpee Wampanoag youth out to gather the wood and help build the structure. While visitors at Mystic Seaport Museum are able to immerse themselves in the cultures represented, tribal youth are learning about conservation and construction methods through this exhibit as well.

To learn more about the “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea” exhibit and the Mystic Seaport Museum, visit mysticseaport.org.

Mystic Seaport Museum | mysticseaport.org, (860) 572-5309

Linda Formichelli has been a freelance writer since 1997. She lives in Raleigh, N.C.

Photos courtesy of Mystic Seaport Museum.