It Takes a Village

As Indigenous-led tourism grows, more truth is told, more lessons are learned, and reconciliation begins

In the vast landscapes of North America lies a cultural tapestry woven by Indigenous peoples over millennia. Today, a growing movement encourages travelers to delve into these rich traditions— not merely as spectators, but as engaged participants. Until recently, it was difficult to know how popular Indigenous tourism was, or how much it was growing. The American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association only began collecting data in 2007, starting with stats about international travelers. “By 2015 there was 180 percent growth in international visitors to Native American communities, which was huge,” says Camille Ferguson, economic development director of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. “And we’re looking at another big bump in growth.”

Why the increase in visitors? The Department of Interior Office of Economic Development is giving $30 million in grants for tourism development within Indian Country, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs provided funds for AIANTA to travel abroad to introduce Indigenous tourism to other countries.

In addition, both domestic and international travelers are becoming more aware of the importance of learning the full story of the U.S. “There is no U.S. history without Indigenous peoples’ history,” says Lorén Spears, Narragansett Tribal Citizen and executive director of the Tomaquag Museum in Exeter, R.I. “It just doesn’t exist.”

Today, through Indigenous America’s compelling narratives, groups are discovering deeper roots and forging meaningful connections.

Perpetuating Cultures Through Immersive Experiences

While tourism is often considered a means to preserve Indigenous cultures, Ferguson counters that it actually helps perpetuate those cultures. She’s been involved in cultural tourism for 35 years; during that time, she worked as a tour guide for a motorcoach company, helped the Sitka Tribe of Alaska develop a Tribal Tour Cultural program, headed up AIANTA as executive director, and served on the board of the Alaska Travel Industry Association. “When I first started, it was not to preserve our culture,” she says. “We were already preserving culture very well in museums. The reason tourism is important is it’s a means to keep our culture alive.”

Traditional ceremonies, songs, and dances are competing with Western sports, entertainment, and video games for Indigenous youths’ attention. “Tourism gives us an opportunity to teach our youth, and then have them be the teachers by dancing, doing their art, and answering visitors’ questions,” says Ferguson. “They’re actually learning, and they are being compensated as well.”

Tour groups themselves help keep Indigenous cultures alive when they’re fully immersed in the present-day experiences of these cultures. “It’s important for visitors to be given the opportunity to participate in a Native museum or cultural center’s hands-on activities so they receive knowledge in many ways—watching, listening, moving, and handling in culturally appropriate ways,” says Michelle Lanteri, Ph.D., museum head curator at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, N.M. “Tactile experiences activate muscle memory.”

Antelope Canyon Tours takes groups on guided tours to the Upper Antelope Canyon and Vermillion Cliffs National Monument.

The Gathering Place stage at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage, Alaska, showcases Alaska Native dancing, Native Games demonstrations, and storytelling.

Exhibits at the Aktá Lakota Museum & Cultural Center connect groups with the culture and traditions of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota people.

The Medicine Wheel Garden at the Aktá Lakota Museum & Cultural Center.

Antelope Canyon Tours: Teaching Navajo History

When groups tour Upper Antelope Canyon, a slot canyon on Navajo land just east of Page, Ariz., they do more than snap photos of the sandstone awash in color or wonder at the rays of sunshine that beam in through openings at the top. They also learn the history of the land and its people from guides who are, in most cases, Navajo or natives of Page. “It’s important we share our history with others so that it may be passed down for future generations,” says Carolene Ekis, president/owner of Antelope Canyon Tours Inc. “Our guides all have different family histories, and it’s really cool to see how we live so close and yet our history is so different.”

Ekis and her company have worked hard to bring tourists to the area. “Before social media, not a lot of people knew about the canyon,” she says. “I went out with the Arizona Office of Tourism on trade missions to different countries to share our beautiful canyon with everyone. It was a long journey to put Antelope Canyon on the map.”

And now that it is on the map, visitors come from all over the world—and take a bit of Navajo history and culture back with them.

John Hall’s Alaska: Expect the Unexpected

Visitors with John Hall’s Alaska have unexpected adventures, whether it be in Alaska or around the world. In small, rural Alaska communities—often 70–90 percent of whom are Alaska Natives—visitors share experiences unique to the culture. Recent tour groups as far north as Utqiagvik and Kaktovik had the opportunity to witness the first subsistence whale harvest of the season. Schools and businesses closed early so the residents could harvest the animal, a true community event.

“There is so much pride and excitement in these communities,” says Chief Operating Officer Elizabeth Hall. “Guests were left breathless by the culture, the lifestyle, and how welcomed they were by the locals during such an important time. It was a once-in-a-lifetime, intimate experience brought to life by the welcoming community and residents.”

Online Exclusive!

Since its founding in 1983, John Hall’s Alaska has been taking groups on immersive, cultural tours of Alaska. Discover what advice Elizabeth Hall, COOO of John Hall’s Alaska, has for operators who are ready to get rolling with indigenous tourism.

Aktá Lakota Museum and Cultural Center: Hands-On Exhibits

For a more contemplative experience, groups can head to the Aktá Lakota Museum and Cultural Center in Chamberlain, S.D. An audio/visual observation area transports viewers into day-to-day Lakota life, and an interactive display provides visitors of all ages with the opportunity to learn and take part in the culture through hands-on exhibits.

For even more inspiration, guests can walk around the Medicine Wheel Garden right next to the Missouri River or meditate among the garden’s native plants. “Each of the four colors and lines in the Medicine Wheel Garden represents an element of the circle of life,” explains Museum Director Dixie Thompson.

The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center offers immersive activities such as art exhibits like Santo Domingo Pueblo/Laguna Pueblo artist Jesse Littlebird’s paintings.

The Soaring Eagle Dance Group of Zuni Pueblo.

Groups can explore North Dakota’s tribal lands on a one-day or multi-day itinerary.

Guided tours and immersive experiences at the Chickasaw Cultural Center in south-central Oklahoma tell the ongoing story of Chickasaw Nation.

Guided tours and immersive experiences at the Chickasaw Cultural Center in south-central Oklahoma tell the ongoing story of Chickasaw Nation.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center: Connecting Through Art, Dance

The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, the gateway to the 19 Pueblos in New Mexico, offers Pueblo and Native American social dances every weekend, all year round. Several of the dance groups invite the audience to join in a Round Dance— an upbeat dance to rhythmic drumming—so visitors can connect to the power of togetherness and community through dance.

The IPCC also facilitates hands-on art workshops for the public, including painting, calligraphy, and even pottery. “Through the power of making art, visitors learn that they are creators and makers of the world around them,” says Lanteri. “These are active moments visitors can continue to reference on their own personal journeys.”

Chickasaw Nation: Immersive Festivals & Events

Chickasaw Country in Oklahoma is brimming with opportunities to be surrounded by Chickasaw culture. The Chickasaw National Capitol, which served as the seat of their government until Oklahoma statehood, is now a museum that’s open to the public. An Artesian Arts Festival in the spring fills downtown Sulphur with First American art, dance, music, and food. And the Chickasaw Annual Festival in the fall features a Chickasaw Princess Pageant, arts and culture awards, a State of the Nation Address, and more.

Even more immersive opportunities include Lunch and Learn sessions; hands-on classes, such as beading workshops; and the annual Holba’ Pisachi’ Native Film Festival in August, where visitors watch First American documentaries, shorts, and feature films.

Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort: The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

In the Great Smoky Mountains of Western North Carolina, groups can fill much of their itinerary at Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort, which is owned by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. There, visitors enjoy 3,000 casino games, 12 dining options, a luxurious 18,000-square-foot spa, 10 retail shops, a sports betting venue, bowling, an arcade, three bars, and the Sequoyah National Golf Club.

If groups have time, they might check out the Cherokee Historical Association’s Oconaluftee Indian Village living history site, which is, according to their website, “So authentic, you may feel funny about bringing a smart phone.” One-hour tours bring guests into the 18th century with historical buildings, traditional Cherokee dancing, and a battle reenactment called Time of War.

Online Exclusive!

The Cherokee Historical Association—and, by extension, the Oconaluftee Indian Village—indirectly benefits from Harrah’s Casino profits through funding from the Cherokee Preservation Foundation. Discover how Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort, Chickasaw Country Tourism, and the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center are empowering their Indigenous communities through economic impact.

The MHA Interpretive Center: Customized Experiences

The MHA Interpretive Center in New Town, N.D., doesn’t just show the history and culture of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara peoples—it also interprets the story of the Great MHA Nation through permanent and temporary exhibitions, living history programs, and special events.

“One of the best attributes of guided tours is the tour guides. On any given day, you may have someone who speaks Mandan, Hidatsa, or Arikara,” says Deanne Cunningham, visitor services, sales, and group travel manager for North Dakota Tourism and Marketing. “They’ll walk you through the cultural center sharing with you what each item is in their language. Then they express what it means to them.”

Also in New Town is Earthlodge Village, a series of reconstructed homes made from wood and earth along the shore of Lake Sakakawea. Visitors can stay the night in an earth lodge, learn about the MHA peoples from cultural interpreters, and enjoy powwows, horse racing events, and dances.

MHA Nation is also perfect for groups looking for a unique cultural trip; tour operators can request custom experiences like dance performances or traditional meals for their guests.

Mystic Seaport: Maritime History

At the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Conn., groups now have the chance to sit in a real dugout canoe or walk inside a wetu—a domed house made with a frame of red cedar—thanks to “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea,” a major exhibition that explores the maritime histories and contributions of Indigenous communities, African civilizations, and people of African descent. The exhibit is part of a broader project called Reimagining New England Histories.

“The dugout canoe was created during a residency with Mashantucket Pequot, Mashpee Wampanoag, Ghanaian, and Togolese boat makers,” says Akeia de Barros Gomes, Ph.D., William E. Cook vice president of the American Institute for Maritime Studies at Mystic Seaport Museum. “Because on both sides of the Atlantic, dugout canoes were made using the same method of hollowing out with fire and water.”

Online Exclusive!

Learn more about the exhibits at Mystic Seaport Museum, the construction of the Wetu, and how both visitors and Mashpee Wampanoag tribal youth are being immersed in cultural experiences.

Groups visiting Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort in North Carolina can learn more about the Cherokee at the Oconaluftee Indian Village and Unto These Hills outdoor drama.

Groups visiting Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort in North Carolina can learn more about the Cherokee at the Oconaluftee Indian Village and Unto These Hills outdoor drama.

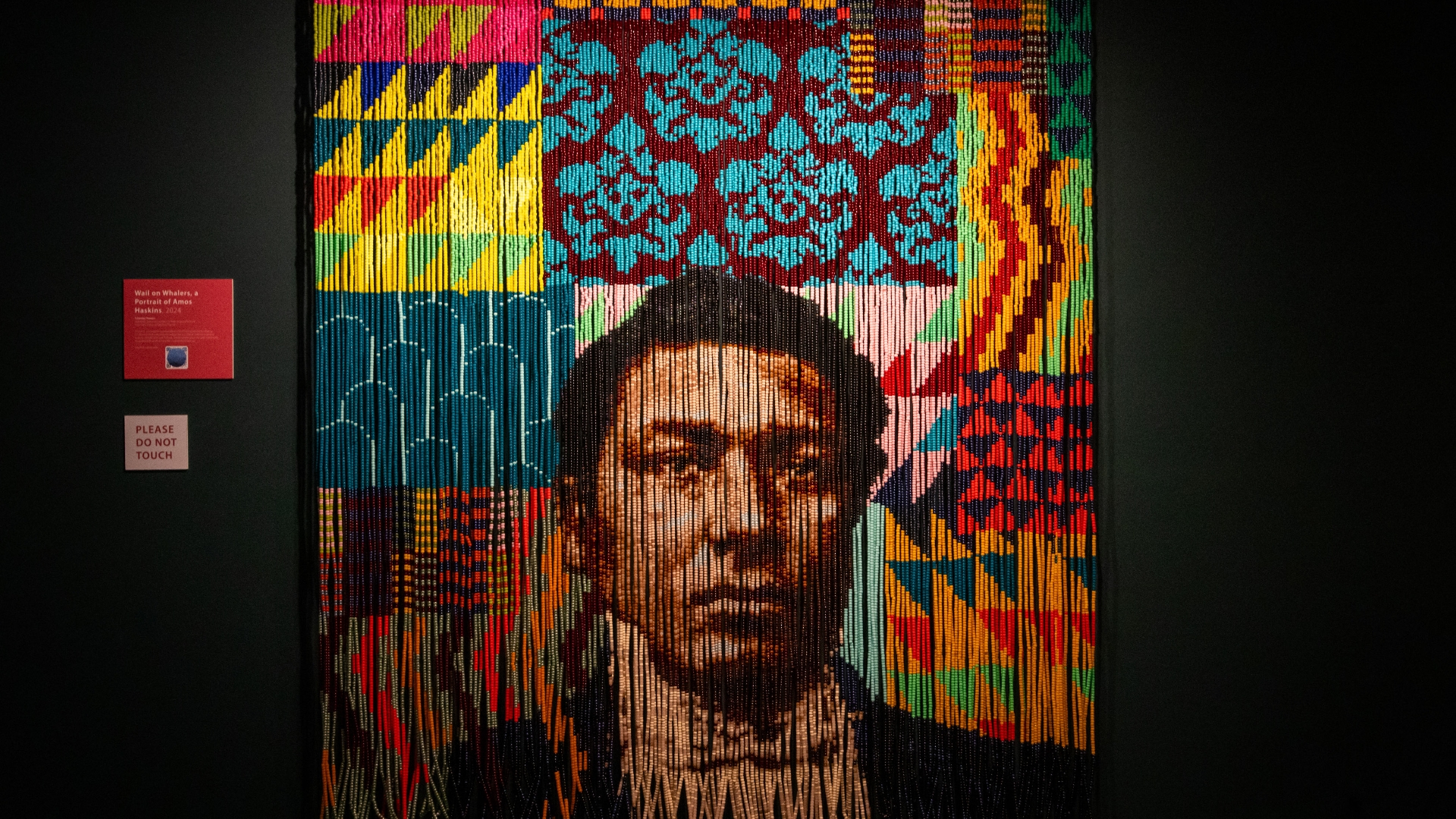

Felandus Thames, 2024 Wail on Whalers, A Portrait of Amos Haskin.

The new “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea” exhibit at Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut tells the maritime histories and experiences of New England’s Indigenous Nations and African-descended peoples.

Christian Goncalves, 2016 Dialogues in the Diaspora.

Education And Awareness

Indigenous tourism doesn’t just offer snapshots of the past and leave visitors to figure out how they connect to the present. Instead, it leads visitors through a history of both darkness and of renewal and empowerment—leading up to today, where peoples’ lives are touched by it all.

In addition to its social dances and workshops, the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center features The Emergence Teachings of Resilience by the NSRGNTS artist collective. This 6-foot-high, three-walled mural on canvas lets groups move through scenes and stories of Pueblo empowerment.

Painted in bright colors in a kawaii, or “cute,” illustrative style, NSRGNTS’ mural shows the connections between Indigenous wisdom of early times and the historical moment of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, and it honors the present and future of contemporary Pueblo cultural practices and community leadership.

The Cherokee Historical Association offers not only the Oconaluftee Indian Village, but also the outdoor drama Unto These Hills, which has been running since 1950. This drama leads viewers through the story of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, from first contact with Europeans through the years after the Trail of Tears—when tens of thousands of Native Americans were forced off their ancestral lands and thousands more were ethnically cleansed by the U.S. government.

Despite this tragic time in history, Unto These Hills showcases “the re-emergence of a people whose spiritual fortitude, social complexities, and human courage will never be broken.”

At the Mystic Seaport Museum’s exhibit “Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea,” visitors learn difficult truths about the past, but with the goal of healing old wounds. The story of New England has always been about its status as a place of refuge for the pilgrims, but this exhibit—and its umbrella project Reimagining New England Histories—“really sees that ‘city upon a hill’ as built upon the backs of Black and Indigenous people,” says de Barros Gomes.

But the message is delivered with empathy. “We don’t just say, ‘Here it is, it’s hard,’” says Spears, who, in addition to her role at the Tomaquag Museum, serves as an advisor for the project. “It’s not filled with hate or with anger, but it’s telling a lot of truths with compassion and grace.”

Adds de Barros Gomes, “Why would we take the opportunity to have an exhibit like this, just to focus on all the awful things that have happened to us? Our stories are so much more than that. There’s actually joy in our stories.”

From live dramas and meditation gardens to art festivals and living history programs, Indigenous tourism is helping keep Native American cultures strong, fostering understanding and healing, providing funds and jobs—and offering a growing number of travelers a new perspective on U.S. history. “America is getting to know America,” says Ferguson. “Tourism is an opportunity for Indigenous peoples to tell their story.”

Linda Formichelli has been a freelance writer since 1997. She lives in Raleigh, N.C.

Photo credits:

INDIAN PUEBLO CULTURAL CENTER; ANTELOPE CANYON: TOBY VISUALS HAWAII; CAROL GOODWIN-COZZEN (AHTNA ATHABASCAN); AKTÁ LAKOTA MUSEUM, ST. JOSEPH’S INDIAN SCHOOL; CAREY TULLY, INDIAN PUEBLO CULTURAL CENTER; JEREMY FELIPE, INDIAN PUEBLO CULTURAL CENTER; TURTLE MOUNTAIN TOURISM; CHICKASAW COUNTRY; VISIT CHEROKEE NC; MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM;